The Snowy Torrents (2017 ) – Book Review and Perspectives

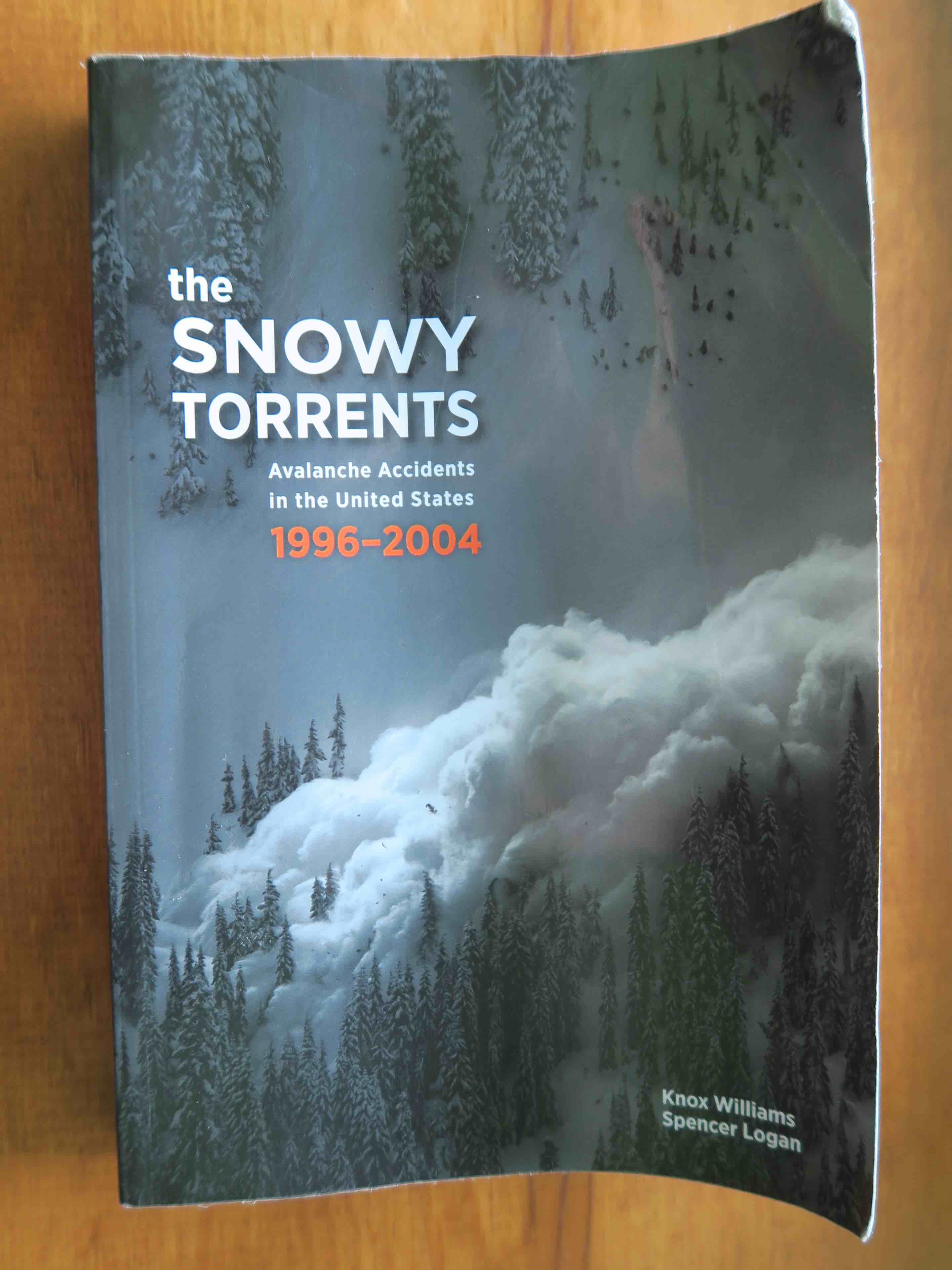

The Snowy Torrents – Avalanche Accidents in the United States 1996-2004 by Knox Williams and Spencer Logan might not make the New York Times Best Seller List, but it is still a priceless, technical compilation of avalanche incidents to add to the backcountry skier’s reading list. Despite the delays of publishing and distributing this large project, I’m glad the authors took their time and used their own creative format to produce the best in the series. The book arrived on shelves a few months ago and after receiving my copy, I thumbed through it for a half hour. I was impressed, and concluded that it would be my only book for a dozen upcoming summer backpacking nights planned for Alaska and the Northern Rockies.

The Snowy Torrents – Avalanche Accidents in the United States 1996-2004 by Knox Williams and Spencer Logan might not make the New York Times Best Seller List, but it is still a priceless, technical compilation of avalanche incidents to add to the backcountry skier’s reading list. Despite the delays of publishing and distributing this large project, I’m glad the authors took their time and used their own creative format to produce the best in the series. The book arrived on shelves a few months ago and after receiving my copy, I thumbed through it for a half hour. I was impressed, and concluded that it would be my only book for a dozen upcoming summer backpacking nights planned for Alaska and the Northern Rockies.

Snowy Torrents is an ongoing series began by Knox Williams as a publication for the Department of Agriculture in the 1950’s. Each subsequent edition has lagged a bit since it can take years to summarize a decade of incidents. While the latest edition may not be “current”, it is the best statistical data available on avalanche incidents in the U.S. Someone had to take the reins on the project, and the pool of qualified people who take the legacy of this series seriously is limited. The critical numbers and graphs compiled add to our collective knowledge as recreationalists and professionals and will be cited in technical papers on snow safety in the future.

Snowy Torrents Timeline

1950 – 1957 – USDA – Knox Williams

1910 – 1966 – USDA – Dale Gallagher

1967 – 1971 – USDA – Knox Williams

1971 – 1979 – AAA – Knox Williams and Betsy Armstrong

1980 – 1986 – Colorado Geological Survey – Nick Logan and Dale Atkins

1987 – 1995 – Missing

1996 – 2004 – Knox Williams and Nick Logan

2005 – 2014 – Pending

I read my first edition of Snowy Torrents in the early 1980’s alongside Snow Sense and Cross-Country Downhill. Each new edition has had a profound effect on my approach to backcountry skiing. The books gave me a better understanding of basic clues to instabilities and the importance of carrying proper gear to perform a rescue or be rescued. These stories will teach and scare you. The more you read the specifics of each incidents, the more you are reminded of how vulnerable the backcountry skier is. Snowy Torrents reinforces this fear to emphasize that longevity in the mountains is not easily attained. After reading this latest edition, I think of myself as a survivor of my time in the mountains, particularly when I reflect on the complicated, dreamy terrain of Valdez and how I have tip-toed around the birth, adrenaline, and hype of big mountain skiiing..

I read my first edition of Snowy Torrents in the early 1980’s alongside Snow Sense and Cross-Country Downhill. Each new edition has had a profound effect on my approach to backcountry skiing. The books gave me a better understanding of basic clues to instabilities and the importance of carrying proper gear to perform a rescue or be rescued. These stories will teach and scare you. The more you read the specifics of each incidents, the more you are reminded of how vulnerable the backcountry skier is. Snowy Torrents reinforces this fear to emphasize that longevity in the mountains is not easily attained. After reading this latest edition, I think of myself as a survivor of my time in the mountains, particularly when I reflect on the complicated, dreamy terrain of Valdez and how I have tip-toed around the birth, adrenaline, and hype of big mountain skiiing..

The book’s forward by American Avalanche Association (AAA) President John Stimberis is excellent. He introduces the difficult challenges faced as we crossed from one century into the next. Knox and Logan have a long history in avalanche work and that passion is evident in their Preface and remarks throughout the book. Each reader will take away what he or she wishes from the book, but one thing is inescapable and that is the sadness for the victims, joy for the survivors and praise for the rescuers.

This particular edition is unique in that it captures a period of stunning growth in backcountry skiing, mechanized-skiing and sledding. In Valdez, there weren’t many of us out there in the backcountry trying to ski away from the crowded Road Run until the rush commenced in 1992. This was also a time when my Thompson Pass Mountain Chalet was busy with skiers and I was skiing myself into exhaustion with 120 days of skiing each season. I humorously and respectfully like to refer to those different periods of Valdez ski history as BC and AC, or Before Coombs and After Coombs.

This particular edition is unique in that it captures a period of stunning growth in backcountry skiing, mechanized-skiing and sledding. In Valdez, there weren’t many of us out there in the backcountry trying to ski away from the crowded Road Run until the rush commenced in 1992. This was also a time when my Thompson Pass Mountain Chalet was busy with skiers and I was skiing myself into exhaustion with 120 days of skiing each season. I humorously and respectfully like to refer to those different periods of Valdez ski history as BC and AC, or Before Coombs and After Coombs.

Alaska stands out as a dangerous place in Snowy Torrents. The state led the nation in fatalities relative to its small population. Today, Alaska is on the cutting edge of avalanche forecasting and education, even across a vast area dotted with tiny towns and mountain passes connected by the internet. Our rate of incidents indicate a downward trend despite increasingly packed trailheads.

The book includes a summary of incidents in Alaska that I had forgotten about. A glance at the table of contents provides a stark reminder of how dangerous Alaska snow can be, listing numerous fatal incidents. Go to the page of any incident and find a condensed or full report by a local avalanche forecaster along with other data such as site pictures and pit profiles.

A number of fatal incidents involving mechanized access occurred near Valdez and are well documented. A current Valdezean was buried in an avalanche at a resort in one state and survived. (You will have to read the book for the person’s name!)

A number of fatal incidents involving mechanized access occurred near Valdez and are well documented. A current Valdezean was buried in an avalanche at a resort in one state and survived. (You will have to read the book for the person’s name!)

Other states show incidents back to back on the same weekend in the same place. As I recall, the professional avalanche community stayed busy trying to figure out how to stop or at least temper the carnage. Discussion on a few incidents were deliberate and emotional on internet platforms such as TelemarkTips and TGR as we tried to save the ski world from itself. During this time, a plethora of extreme ski movies trashed our sense of vulnerability while avalanche professionals were loud and clear about the dangers. Canada also experienced the same issues during this period.

Valdez was “As Sick As It Gets” according to the cover of Powder Magazine and the masses were discovering big mountain skiing, fat skis and 800cc’s across Alaska and the Western U.S. in the mid-90’s. But, avalanches don’t care how big the mountain is as far as defining when and where a slab of snow will slide and kill someone. From the smallest avalanche just 100 feet from a trailhead that killed a ski-tourer to the massive multiple slides that killed six Alaskan sledders in Turnagain Pass, a profoundly important pattern surfaces in nearly every incident; victims ignored obvious clues or lacked the education to identify basic clues. A large number of deaths involved people carrying no beacons, probes or shovels, something unheard of today.

Snowy Torrents documents a dozen or so incidents involving individuals with high levels of experience and education. Those incidents not only involved ignoring clues, but also complacency. This is worth noting for both Valdez locals and non-resident guides who have skied or sledded here for 20 years. In 1990, there were only a couple of locals who had skied the peaks of Thompson Pass. The cohort size of those with 25 years of experience is increasing and is now vulnerable to complacency. There is anecdotal evidence that the members of another cohort, those who have more than three decades of experience under their belts(and not just Alaska), may create a another rising bell-curve at the end of the common age/fatality graphs with which we are familiar.

Valdez is home to some of the most skilled people in the world because our terrain demands the right call every time. We don’t have bunny slopes and there is not much room between slopes that can or can’t slide. Our avalanche terrain hits you when you open your car door whether at the Pass or under your house’s roof. One of the reasons I quit guiding was the fear of creeping complacency. My cumulative days of being exposed to avalanche terrain over a lifetime and the overall risk to clients worried me. I ski as much as I can today, but not all the time and no longer with the obsession that continually pushed me to the edges of safety and stability.

Valdez is home to some of the most skilled people in the world because our terrain demands the right call every time. We don’t have bunny slopes and there is not much room between slopes that can or can’t slide. Our avalanche terrain hits you when you open your car door whether at the Pass or under your house’s roof. One of the reasons I quit guiding was the fear of creeping complacency. My cumulative days of being exposed to avalanche terrain over a lifetime and the overall risk to clients worried me. I ski as much as I can today, but not all the time and no longer with the obsession that continually pushed me to the edges of safety and stability.

As with books on tragedy, it’s best in small doses as the incidents become all too similar. It’s melds into the same story over and over and chapter after chapter. The only constant differences are the names of the victims. If you read the stories and learn the lessons, the book will help you as much as the dozens of book on how to avoid getting caught in the first place.

Matt Kinney

Valdez, AK

September 16, 2017

To order the book: